After the coffee harvest and processing, green coffee can be decaffeinated. There are various methods for this, ranging from the use of chemicals to “natural” decaffeination with water and activated carbon filters. What all methods have in common is that they do not decaffeinate to 100%, but only to 94% and upwards. The EU stipulates that coffee beans sold as caffeine-free must not contain more than 0.3% residual caffeine.

The method used for our low and decaffeinated coffees promises a residual caffeine content of <0.1%. In this article we explain how this is achieved.

Caffeine makes you awake, sure, but how does it actually work? The answer can be found in the brain. The caffeine docks onto a specific receptor there and blocks it from the molecule adenosine, which usually resides there. Instead of feeling sleepy and sluggish, we become awake and energized as long as the caffeine works. It causes the body to produce adrenaline because it senses danger. So we put our body in a kind of stressful state.

Like other drugs, coffee also increases dopamine release. This makes us feel good. But the same applies here: the dose makes the poison. Too much caffeine can cause anxiety and disrupt sleep. Increased heart rate and sweat production are also common unpleasant side effects that coffee fans can relate to.

The half-life of caffeine in the human body is approximately 6 hours. If we drink a cup of coffee at 4 PM, there is still a lot of caffeine in the body at 10 PM, which can potentially disrupt sleep because it continues to block the receptors for adenosine.

The decaffeination accident

Decaffeinating coffee has its origins in the early 20th century. In 1903, coffee entrepreneur Ludwig Roselius struggled with a shipment of coffee that was exposed to seawater. It had significantly less caffeine than usual. Recognizing the business potential, Roselius set out to find a more reliable and economical way to decaffeinate coffee.

He finally developed a process, in which the pores of the green coffee beans were opened with a salt steam bath and then largely freed of caffeine using benzene. However, since benzene is considered to be potentially carcinogenic, it soon had to give way to other chemical substances.

Today there are four main methods used for decaffeination. Two of these methods use a solvent: either dichloromethane or ethyl acetate (ethyl acetate). Although it may sound unhealthy, according to the relevant control authorities, coffee in the end product is harmless to health and can no longer be detected.

Let's take a closer look at these methods.

Solvent-based decaffeination

In order to dissolve caffeine from green coffee using dichloromethane or ethyl acetate, the pores of the beans must first be opened. To do this, they go into a steam bath. Once the pores are open, the coffee beans are “washed” several times with a chemical solution. The caffeine molecules bind to the dichloromethane or ethyl acetate. The beans are then put into a water steam bath again to remove the chemicals.

Some companies also choose to avoid direct contact with the solvents altogether. In these variants of solvent-based decaffeination, the green coffee beans are soaked in water. Caffeine and other water-soluble substances escape and pass into the water. The coffee is then removed from the enriched water.

Now the solvents come into play and are added. As described above, in this variant they also bind the caffeine molecules. The solution is then heated, causing the chemicals and thus also the bound caffeine to evaporate. Now the coffee beans go back into the water bath to absorb the remaining substances.

Solvent-free decaffeination

There are also broadly two methods for solvent-free decaffeination. The older and less risky method became known under the name Swiss Water Process. Although it was developed in Switzerland in the 1930s, it has only been used commercially on a large scale since the late 1980s.

The organically certified company Swiss Water Decaffeinated Coffee Inc. operates its facilities in the Canadian state of British Columbia. While the method itself is probably one of the most environmentally friendly, this balance is somewhat clouded because the green coffee to be decaffeinated always has to make a stopover in Canada.

This is how the Swiss Water Process works

With the gentle Swiss Water process and imitators such as the Mountain Water Process, the green coffee is soaked in water. Water-soluble substances, including caffeine, pass into the water. The first batch of green coffee is then disposed of and the caffeine is filtered out of the water.

The remaining components of the coffee remain. This is important so that in the second batch only the caffeine is removed from the beans, which is then filtered out of the water again with activated carbon. This is possible because the water can only dissolve a certain concentration of substances from the coffee beans before it is saturated. What’s left is the decaffeinated green coffee.

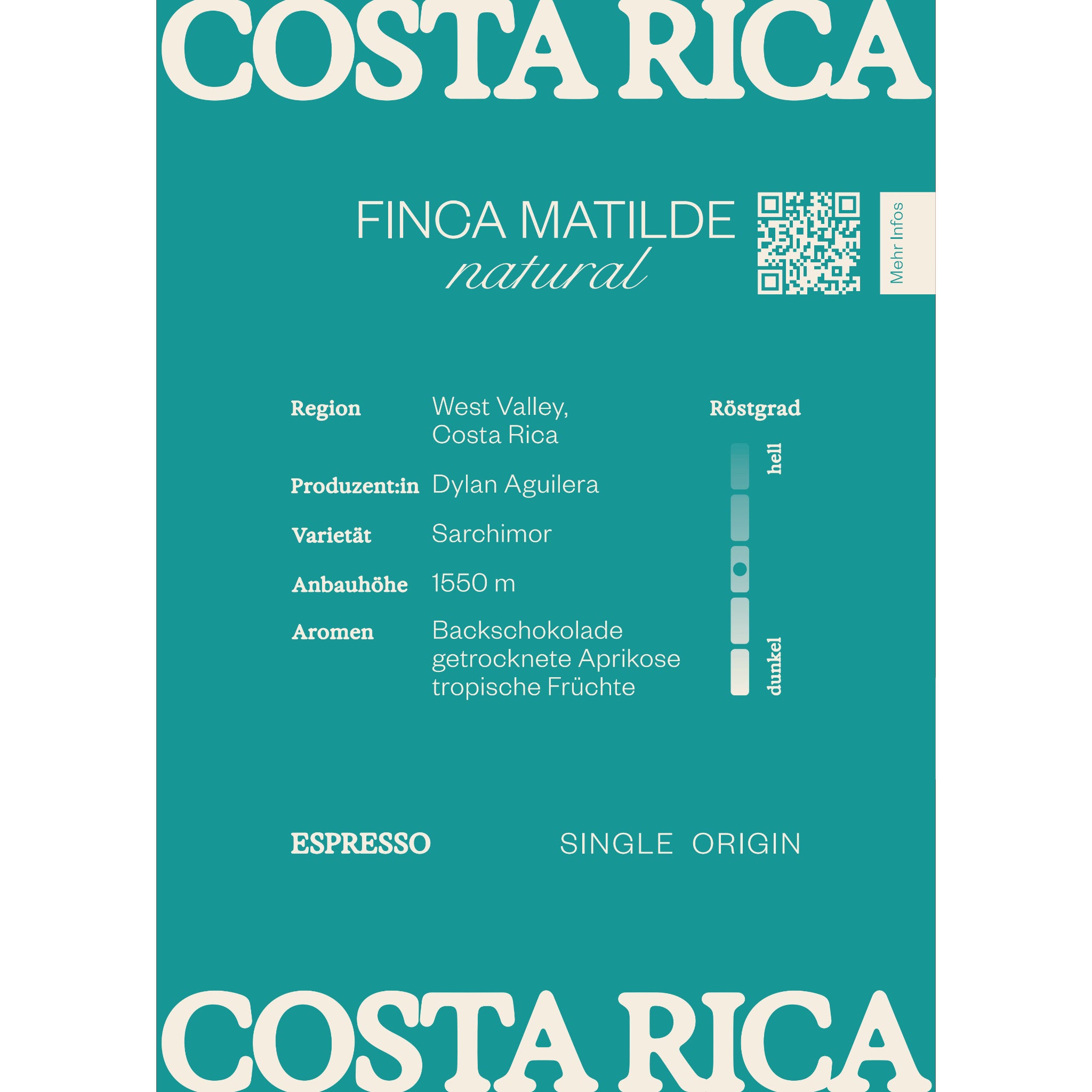

The company claims that this method removes 99.9% of the caffeine from the beans. Our decaffeinated coffee DECAF Mexico is processed using the Mountain Water Process. The reason for this is that the Descamex company is located just four kilometres from Benjamin's family farm. This means that we avoid unnecessarily long, additional transport routes.

Decaffeination with liquid CO2

The second relevant method we will discuss here uses liquid carbon dioxide. Soaked coffee beans go into a stainless steel tank, which is then sealed. Then the liquid CO2 is added until a pressure of approx. 69 bar is reached. The caffeine is extracted from the beans in a similar way to the solvents discussed previously.

This process is called destraction. The liquid CO2 and caffeine then go into a separate container where the high pressure is reduced again. This results in the liquid CO2 changing into its gaseous state. In the process, CO2 and caffeine separate, meaning the former can then be reused.

How much caffeine is actually removed from the beans during decaffeination depends on the method chosen. For our caffeine-free coffee we use the Swiss Water or Mountain Water method. The providers promise 99.9% less caffeine.

Low caf instead of no caf

In addition to caffeine-free coffee beans, low-caffeine coffee is currently on the rise. These are usually coffee plants, which naturally contain less caffeine. However, there is also the option of mixing decaffeinated beans with caffeine ones.

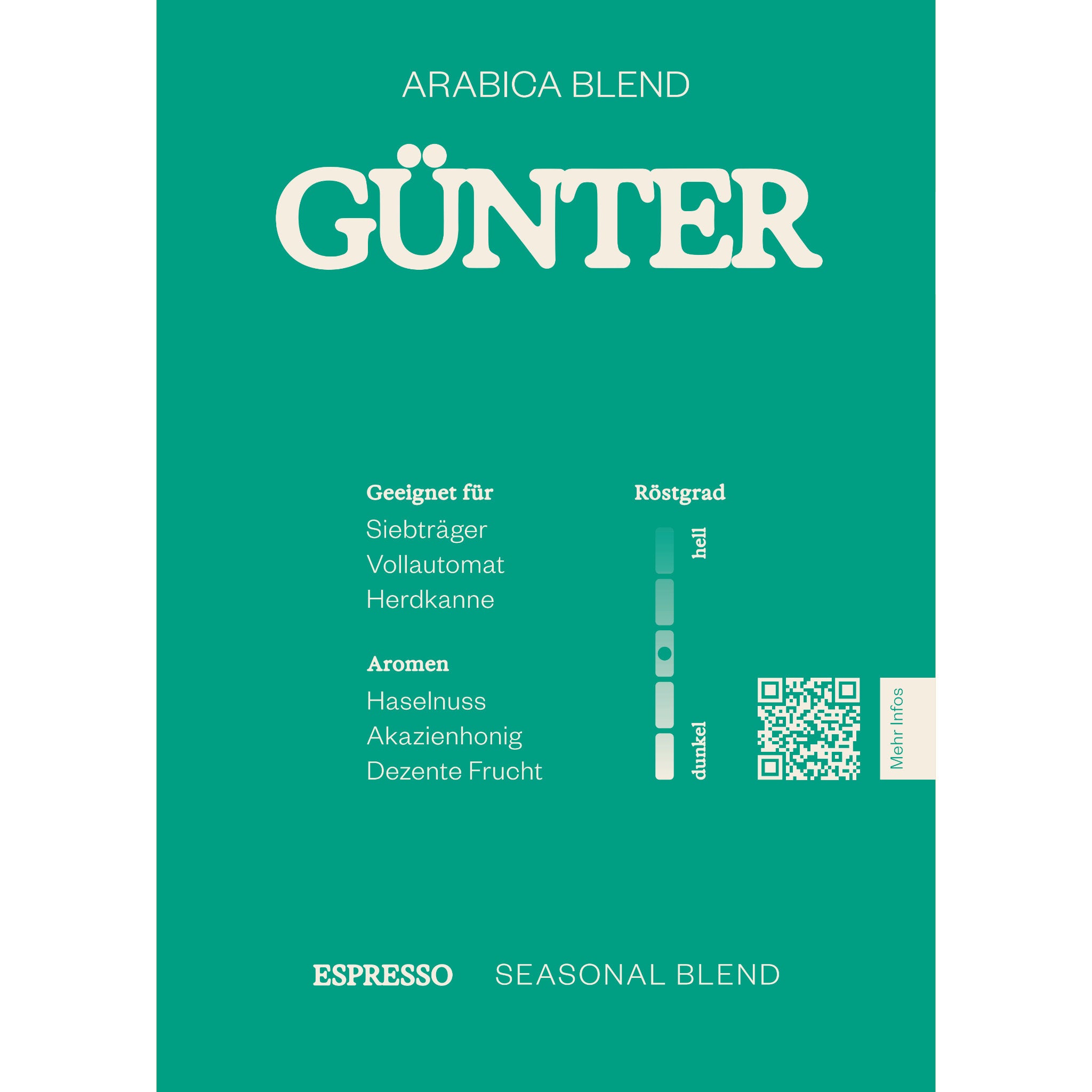

We take this approach with our Lowcaf blend, for which we mix the same coffee - one decaffeinated and one untreated - in equal parts. You can read more about this in our article on Lowcaf.

2 comments

Nico von Günter Coffee Roasters

Hallo Oliver,

vielen Dank für deinen Kommentar und den Hinweis. Zwar kann man vielerorts lesen, dass der Restgehalt an Koffein in entkoffeiniertem Kaffee laut EU maximal 0,1 % betragen darf, allerdings habe ich dafür keine Quelle gefunden. Die 0,3 % stammen aus der Richtlinie 1999/4/EG des Europäischen Parlaments, beziehen sich aber auf löslichen oder bereits gelösten Röstkaffee in flüssiger Form. Falls du eine Quelle hast, ergänze ich diese gerne im Text. Den entsprechenden Hinweis aus meinem Kommentar habe ich auch im Artikel ergänzt.

Liebe Grüße

Nicolas

Hallo Oliver,

vielen Dank für deinen Kommentar und den Hinweis. Zwar kann man vielerorts lesen, dass der Restgehalt an Koffein in entkoffeiniertem Kaffee laut EU maximal 0,1 % betragen darf, allerdings habe ich dafür keine Quelle gefunden. Die 0,3 % stammen aus der Richtlinie 1999/4/EG des Europäischen Parlaments, beziehen sich aber auf löslichen oder bereits gelösten Röstkaffee in flüssiger Form. Falls du eine Quelle hast, ergänze ich diese gerne im Text. Den entsprechenden Hinweis aus meinem Kommentar habe ich auch im Artikel ergänzt.

Liebe Grüße

Nicolas

oliver

Hallo!

Woher kommt der %-Wert im obigen Artikel – Auszug: “Die EU schreibt vor, dass als koffeinfrei verkaufte Kaffeebohnen nicht mehr als 0,3 % Restkoffein enthalten dürfen.”

Meines Wissens nach lautet der korrekte Wert 0,1 %.

LG

Hallo!

Woher kommt der %-Wert im obigen Artikel – Auszug: “Die EU schreibt vor, dass als koffeinfrei verkaufte Kaffeebohnen nicht mehr als 0,3 % Restkoffein enthalten dürfen.”

Meines Wissens nach lautet der korrekte Wert 0,1 %.

LG